Article: Juliane Biermann, Steffen Höchel, Holger Heidenreich

Pharmacotherapy of Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma (mRCC): 2017 Update

Department of Urology (Chief Physician: Colonel (MC) H. Heidenreich, MD) of the Berlin Bundeswehr Hospital (Hospital Commander: Commodore (MC) K. Reuter, MD)

Summary

Over the past ten years, the introduction of targeted therapy has led to dramatic changes in the treatment of metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). For the first time, new substances have been able to demonstrate an advantage in overall survival, while others show promising results in combination therapy.

This article provides an overview of all substances currently available, a rationale of their use in clinical practice and, based on drug approval studies, an insight into their mechanisms of action and effectiveness as well as their possible use in sequenced therapy.

Keywords: clear-cell renal cell carcinoma, targeted drugs, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, checkpoint inhibitors, sequencing treatment

Background

With about 15,000 new cases in 2013, renal cell carcinoma (RCC) ranks seventh among all cancers in terms of incidence in Germany [22]. At the time of initial diagnosis, metastases are found in 25 to 30% of patients [7]. A further 20 to 30% experience a relapse after nephrectomy, mostly within the first three years [1].

The share of renal cell carcinoma in all cancer deaths is 2.6% for men and 2.1% for women. In Germany, 5,247 people (3,096 men and 2,151 women) died of a malignant kidney tumour in 2010 [22]. In spite of the great progress made over the last 10 years using targeted substances against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), the majority of patients will develop resistances against VEGF- and mTOR-targeted therapeutic agents. New strategies are needed to overcome resistances and to achieve long-term remission.

The urology departments of the Bundeswehr hospitals provide not only surgical expertise (preserving organ function, minimally invasive methods), but also face the current challenge of this innovative tumour pharmacotherapy.

Methods

In order to perform a best-evidence synthesis, we searched PubMed for the keyword "metastatic renal cell carcinoma" with a focus on reviews published in 2017. We excluded, among others, non-randomised studies, case reports, studies with a negative result as well as articles on substances that we personally verified were not approved by the European Medicines Agency. The guidelines of the European Association of Urology (EAU), of the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) and the German S3 medical guideline as well as the relevant references were included.

Results

Approved Substances

A search for the term "metastatic renal cell carcinoma" produced a total of 13,919 results published between 1946 and 12 April 2017. We identified ten studies that met the criteria and led to the examined substances being approved in Europe. Table 1 shows the relevant results. The guidelines of the EAU, of the ESMO and the German S3 medical guideline included 396, 54 and 703 references to the literature, respectively. We further found one review published in 2017.

The tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) pazopanib [20] and sunitinib [16], the mTOR inhibitor temsirolimus [9] as well as the VEGF antibody bevacizumab in combination with interferon-α [3] were approved for first-line therapy. The tyrosine kinase inhibitors sorafenib [5], axitinib [12], cabozantinib [20] and lenvatinib in combination with everolimus [11], the mTOR inhibitor everolimus [15] and the checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab [14, 21] were approved for second-line therapy. In first-line therapy, only temsirolimus was able to demonstrate an advantage in overall survival. Cabozantinib and nivolumab were able to do so in second-line therapy. Lenvatinib in combination with everolimus was approved by the European Medicines Agency on the basis of a phase 2 study.

Table 1: Summary of the results of the drug approval studies

| Substance | Comparison | PFS (Months) | P-value | OAS (Months) | P-value |

| Sunitinib | Interferon | 11 | <0,001 | 26,4 | 0,051 |

| Bevacizumab | Interferon | 10,2 | <0,0001 | 23,3 | 0,1291 |

| Temsirolimus | Interferon | 5,5 | 0,0001 | 10,9 | 0,0069 |

| Pazopanib | Placebo | 9,2 | <0,0001 | 22,9 | 0,224 |

| Sorafenib | Placebo | 5,5 | <0,01 | NR | NA |

| Everolimus | Placebo | 4,0 | <0,0001 | NR | NA |

| Axitinib | Sorafenib | 8,3 | <0,0001 | 20,1 | 0,3744 |

| Nivolumab | Everolimus | 4,6 | 0,11 | 25,0 | 0,002 |

| Cabozantinib | Everolimus | 7,4 | <0,001 | 21,4 | 0,0003 |

| Lenvatinib&Everolimus | Monotherapie | 12,8 | 0,029 | 25,5 | 0,00647 |

PFS = progression-free survival; OAS = overall survival

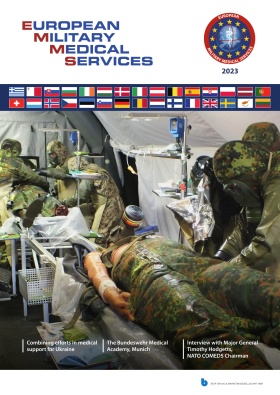

Figure 1: Cellular points of attack in the targeted treatment of mRCC [6].

Mechanisms of action

Figure 1: Cellular points of attack in the targeted treatment of mRCC [6].

Mechanisms of action

mTOR inhibitors such as temsirolimus or everolimus directly affect the signal transduction of the tumour cell. The tyrosine kinase inhibitors sorafenib, sunitinib, pazopanib and axitinib inhibit the tyrosine kinase of VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) and PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor) and thus stop phosphorylation and subsequent activation. The newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors cabozantinib and lenvatinib have similar mechanisms of action.

Figure 2: Mechanism of action of Nivolumab as checkpoint inhibitor [19]: PD-1 on the T cell binds to PD-L1 on the tumour cell, thus inactivating the T cell (above). Nivolumab (monoclonal antibody) prevents binding of PD-1 to PD-L1 (below).

Figure 2: Mechanism of action of Nivolumab as checkpoint inhibitor [19]: PD-1 on the T cell binds to PD-L1 on the tumour cell, thus inactivating the T cell (above). Nivolumab (monoclonal antibody) prevents binding of PD-1 to PD-L1 (below).

The VEGF antibody bevacizumab in combination with IFN binds to VEGF so that activation of the VEGF receptor is no longer possible.

All mentioned targeted drugs inhibit angiogenesis by inhibiting signal transduction in the tumour cell. As the existing tumour blood vessels recede and new vessels cannot develop, the tumour is supplied with less oxygen. This stops tumour growth and can even lead to necrosis of the cell. Figure 1 illustrates the different modes of action of the drugs described above.

As a so-called checkpoint inhibitor, nivolumab binds to the programmed death (PD) receptors on T cells to stop interaction with the ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2, which are expressed by the tumour cells and which otherwise protect the tumour cell against an immune response. Nivolumab thus causes the destruction of tumour cells through activation and proliferation of T cells (Figure 2 below).

Discussion

With the introduction of targeted drugs, enormous progress has been made in the treatment of metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma (mRCC) over the past 10 years. Since 1985, unspecific immunotherapeutics had been used to treat this tumour that is neither chemo-sensitive nor hormone- or radio-sensitive. This group includes cytokines interferon-⍺ (IFN) and interleukin-2 [18]. Only patients with a good risk profile, however, profited from this therapy, which also involved a wide range of adverse effects [12].

Likewise, not all patients can profit from targeted therapy. In 2009 and 2013, HENG et al. were able to categorise subgroups characterised by very different prognoses. This led to the establishment of the Heng Scores (IMDC risk factors), which replaced the Motzer Criteria (Tables 2 and 3) [8].

Table 2: IMDC Risk Factors (International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium) [8]

| Elevated LDH (>1.5 of normal value) |

| Anaemia |

| Thrombocytosis |

| Neutrophilia |

| Hypercalcaemia |

| Karnofsky performance <80%) |

| Fast progression (<1 year from diagnosis to treatment) |

Table 3: Risk groups based on IMDC risk factors and prognosis [8]

| Number of risk factors | Median overall survival | |

| favourable | 0 | 43,2 months | |

| intermediate | 1-2 | 22,5 months | |

| poor | 3-5 | 7,8 months |

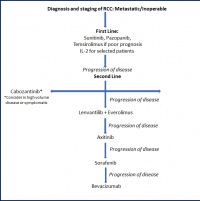

Figure 3: Pharmacotherapy of clear-cell mRCC, ESMO 2016 (modified from [4])

Figure 3: Pharmacotherapy of clear-cell mRCC, ESMO 2016 (modified from [4])

Especially patients in the intermediate or poor risk groups had poor survival results even in the TKI era. This makes sense in light of the results of approval studies in which only temsirolimus was able to generate a survival advantage, and only for patients of the poor risk group.

All other tyrosine kinase inhibitors and antibodies may improve progression-free survival but not overall survival. Two targeted drugs introduced in 2016 were the first to be able to demonstrate improved overall survival, leading to cabozantinib and nivolumab being approved for second-line therapy. In a subgroup analysis, both substances showed significant advantages over everolimus even in a poor risk situation with osseous or visceral metastases [13]. Another subgroup analysis revealed pre-treatment to have a significant influence on results: nivolumab after pazopanib and cabozantinib after sunitinib achieved significantly better results than vice versa [13].

Combination Therapies

Across all risk groups, combination therapies are rarely used because of the lack benefit and the high rate of adverse effects [10]. Only bevacizumab with IFN as well as lenvatinib with everolimus are considered established combinations.In case of progression, recourse to second-line treatment, then third-line treatment is possible (so-called sequencing of treatment). The choice of drugs in that case depends on pre-treatment (Figure 3).

Therapy Monitoring and Management of Adverse Effects

Throughout systemic therapy, assessments should be performed to see if the tumour responds to treatment. Since prospective data about the best time for such assessment are unavailable, cross-sectional images should be taken every 6–12 weeks to assess progression, much like during drug approval trials [10].

Since the mechanisms of action of targeted drugs are completely different from classic chemotherapy, the attending physician faces new challenges when typical adverse effects occur (Table 4). It is vital to quickly identify these adverse effects as such and transfer patients to a facility that can provide oncological expertise, which for soldiers, as a rule, is the urology department of a Bundeswehr Hospital. Symptomatic therapy is usually enough to treat mild to moderate adverse effects. If adverse effects are severe, possible approaches are to interrupt therapy, reduce doses or modify the regimen.

Table 4: The 5 most common adverse effects of targeted drugs (according to drug information)

| Wirkstoff/-kombination | Häufigste Nebenwirkungen | ||||

| Sorafenib | diarrhoea | rash | fatigue | hand-foot-syndrome | alopecia |

| Sunitinib | diarrhoe | fatigue | nausea | stomatitis | hypertension |

| Bevcizumab + interferon α-2A | fever | anorexia | fatigue | bleeding | asthenia |

| Temsirolimus | asthenia | rash | anaemia | nausea | anorexia |

| Everolimus | stomatitis | rash | fatigue | asthenia | diarrhoea |

| Pazopanib | aiarrhoea | hypertension | change in hair color | nausea | anorexia |

| Axitinib | diarrhoea | hypertension | fatigue | anorexia | nausea |

| Nivolumab | fatigue | nausea | itching (immunemediated) | diarrhoea (immunemediated) | anorexia |

| Cabozantinib | diarrhoea | fatigue | nausea | anorexia | hand-foot-syndrome |

| Lenvatinib + Everolimus | diarrhoea | fatigue | hypertension | nausea | cough |

Figure 4: Further development of sequenced therapy of mRCC on the basis (modified from [13])

Conclusions

Figure 4: Further development of sequenced therapy of mRCC on the basis (modified from [13])

Conclusions

Thanks to the further development from unspecific to targeted drugs, pharmacotherapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma has over the last ten years improved the quality of life as well as progression-free and, since the development and introduction of new substances, even overall survival rates of patients.

With the current German S3 medical guideline for diagnosis, therapy and follow-up care of renal cell carcinoma (published September 2015, revised in April 2017) and the guidelines of the EAU and the ESMO, which were updated in 2016, there are three equivalent guidelines that differ in merely a few details (figure 4).

Key Statements

- Pharmacological sequenced therapy of metastatic renal cell carcinoma is based on prognosis risk estimation.

- For first-line therapy, the tyrosine kinase inhibitors sunitinib and pazopanib as well as bevacizumab in combination with interferon-⍺ are available. In poor risk situations, treatment with temsirolimus, sunitinib or pazopanib is indicated.

- The checkpoint inhibitor nivolumab or the tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib are used in second-line therapy. Other tyrosine kinase inhibitors (axitinib, sorafenib) are also an option.

- Cabozantinib and nivolumab are recently introduced substances that are the first to have been demonstrated to improve overall survival rate.

- The constant development of pharmacotherapy leads to new guidelines and therapy notes that should be integrated in the treatment concept.

Literature

- Athar U, Gentile TC: Treatment options for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a review. The Canadian Journal of Urology 2008; 15(2): 3954 - 3966.

- Choueiri TK et al.: Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma (METEOR): final results from a randomised, open- label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncology 2016; 17: 917 - 927.

- Escudier B et al.: Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet Oncology 2007; 370: 2103 - 2111.

- Escudier B et al.: Renal cell carinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, teatment and follow-up. Annals of Oncology 2016; 27(5): 58 - 68.

- Escudier B et al.: Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2007; 356(2): 125 - 134.

- Greef B, Eisen T: Medical treatment of renal cancer: new horizons. British Journal of Cancer 2016; 115: 505 - 516.

- Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, Russell MW, Charboneau C: Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature review. Cancer Treat Rev 2008; 34(3): 193 - 205.

- Heng DY et al.: External validation and comparison with other models of the international metastatic renal-cell carcinoma database consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncology 2013; 14(2): 141 - 148.

- Hudges G et al.: Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine 2007; 356(22): 2271 - 2281.

- Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft, Deutsche Krebshilfe, AWMF): Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Nierenzellkarzinoms, Langversion 1.2, 2017, AWMF Registernummer: 043/017OL, http://leitlinienprogrammonkologie.de/Nierenzellkarzinom.85.0.html (last accessed on 24 July 2017).

- Ljungberg B, Albiges L, Bex A et al.: Guidelines on renal cell carcinoma. European Association of Urology 2016; https://uroweb.org/guidline/renal-cell-carcinoma (last accessed on 24 July 2017).

- Motzer RJ et al.: Axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: overall survival analysis and updated results from a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncology 2013; 14(6): 552 - 562.

- Motzer RJ et al.: Lenvatinib, everolimus, and the combination in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, phase 2, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncology 2015; 16: 473 - 482.

- Motzer RJ et al.: Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine 2015; 373: 1803 - 1813.

- Motzer RJ et al.: Phase 3 trial of everolimus for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results and analysis of prognostic factors. Cancer 2010; 116(18): 4256 - 4265.

- Motzer RJ et al.: Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2007; 356(2): 115 - 124.

- Postow MA et al.: Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2015; 33(17): 1974 - 1982.

- Rosenberg SA et al: Prospective randomized trial of high-dose interleukin-2 alone or in conjunction with lymphokine-activated killer cells for the treatment of patients with advanced cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1993; 85(8): 622 - 632.

- Society for immunotherapy of cancer: Patient resource: Understanding Cancer Immunotherapy. Patient Ressource 2015; 2nd Edition: 4.

- Sternberg CN et al.: Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2010; 28(6): 1061 - 1068.

- Zarrabi K et al.: New treatment options for metastatic renal cell carconoma with prior anti-angiogenesis therapy. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2017; 10: 38.

- Zentrum für Krebsregisterdaten im Robert Koch-Institut: Bericht zum Krebsgeschehen in Deutschland 2016. http://www.krebsdaten.de/Krebs/DE/Content/Publikationen/Krebsgeschehen/Krebsgeschehen_node.html (last accessed on 19 June 2017)

Conflict of interest:

In 2016, Dr Biermann was paid a fee by Novartis for her participation in an advisory board.

Manuscript data:

Submitted: 4 April 2017

Revised version accepted: 24 July 2017

Citation:

Biermann J, Höchel S, Heidenreich H: Medical treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) – Update 2017. Wehrmedizinische Monatsschrift 2017; 61(7): 196 - 200.

Corresponding author:

Major (MC) Juliane Biermann, MD

Berlin Bundeswehr Hospital

Department XI of Urology

Scharnhorststr. 13, 10115 Berlin

E-Mail: julianebiermann@bundeswehr.org

Eine Deutsche Version dieses Artikels finden Sie unter:

http://wehrmed.de/article/3025-medikamentoese-therapie-des-metastasierten-nierenzellkarzinoms-mrcc-update-2017.html

Date: 11/24/2017

Source: Wehrmedizinische Monatsschrift 2017/8