Article: L. A. LAMPL, B. HOSSFELD (GERMANY)

The German Concept of Intercontinental Intensive Care

In addition to the special aspects of military evacuation, natural disasters or terrorist attacks often result in so many victims at one time that the capacities of civilian air ambulances are quickly exceeded. Governmental, e.g. military back-up for such situations may be one of the answers. This article describes the concept for Strategic Airmedevac of the German Armed Forces.

Introduction

The transport of severely injured or critically ill patients on a large scale requires both, medical equipment which has to be permanently adapted to the national standard, and qualified intensive-care personnel.

At present, in Germany, the aircraft used for such deployments are the C-160 Transall, Airbus A-319 and Airbus A-310, which, if necessary, can be equipped with three, two or six intensive-care “patient transportation units” (PTU), respectively. The PTU corresponds to the technical equipment of the intensive care unit of a level-1-trauma centre enabling intensive-care therapy on a high standard even during long-haul flights.

The application of the equipment, the features of the long-haul air transport and the special situation of a military deployment generate special demands for the qualification of the personnel assigned.

Primarily planned for the repatriation of injured or seriously ill soldiers, during recent years this concept has also proven essential for the medevac of civilian victims after mass casualties, natural disasters or terroristic attacks worldwide.

The mission and its origins

The start of the organised repatriation of ill and injured German soldiers or members of allied forces coincided with Germany’s military engagement on the territory of the former Yugoslavia. The theatres of operations were, from summer 1995, initially in Croatia, then from winter 1996/1997 in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and later in Kosovo.

There had already been individual repatriation flights whose purpose had, however, tended to be the provision of military assistance in cases of civil emergencies of an exceptional kind.

Over the past 21 years, Germany’s military engagement has grown considerably, both in terms of its type and scope, and today involves theatres of operation in South Eastern Europe, Africa and Asia.

All German federal governments have attached particular importance to the medical service component of operational contingents. On the one hand, this component follows the so-called “maxim of the medical services”, which states that each soldier in the country of deployment must receive (immediate and effective) medical treatment if sick or wounded. This effectively corresponds to the German domestic standard. On the other hand, it involves the field hospitals and rescue centres set up for this purpose, as well as the provision of care to friendly armies and organisations (e.g. UN, OSCE, international police services, etc.), and also, as far as possible, humanitarian medical aid for the civil population as a confidence-building measure.

The field hospital is designed for the acute, and often life-saving treatment of potentially lethal injuries and diseases (so-called “damage control concept”), but not for lengthy subsequent treatment until full recovery. This is why acute health care in the country of deployment needs to be strengthened by a stringent concept that enables the rapid and, at times, time-critical repatriation of those affected, since only then can the above-mentioned maxim of the medical services be followed.

In the GER Armed Forces, the mission for transport of the wounded under strategic conditions bears the name STRATAIR-MEDEVAC. This covers not only the capability for transportation and medical provision for a number of patients that goes beyond the civilian norm, but also the requirement that patients whose life is at risk for longer periods of time be transported safely over great distances under the conditions of an intensive care unit.

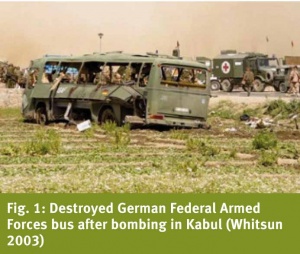

Developed, structured and organised primarily for the military (Figure 1), the capacities and capabilities of the German Federal Armed Forces are also, by way of administrative assistance, made available in the event of exceptionally serious civil mass casualties (Figure 2).

Deployed aircraft

Depending on the distance, number of patients and tactical requirements, 3 different types of aircraft can be used for (intensive-care) medium and long-distance

transportation:

- C-160 Transall

- Airbus A-319

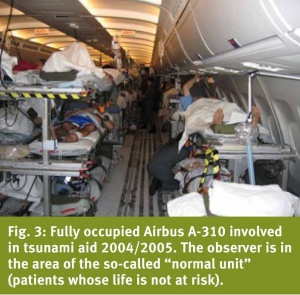

- Airbus A-310, often referred to colloquially as the “flying hospital” (Figure 3)

The objectives and the capabilities and skills required to achieve them can be characterised as follows:

- Uninterrupted continuation of the therapy required for the individual patient, and where appropriate, also intensive care

- Possibility of the intensification of therapy on board

- Sufficient reserves of material for long flights

- Constant readiness

The intensive-care workplace

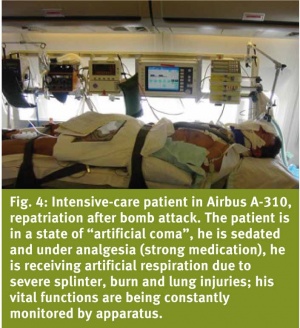

At the heart of medical equipment for all the above types of aircraft is the intensive-careworkplace (patient transport unit [PTU]), whose equipment and abilities are equivalent to those of a ground based intensive care unit. Such intensive-care workplaces are incorporated into the Airbus A-319 2 x, in the C-160 Transall up to 3 x and the Airbus A-310 6 x (Figure 4).

Medical personnel and their selection

In addition to the aircrew, and depending on the mission and the number of patients, there is a large team that may vary in size, which includes aeromedical components as well as an emergency medical technician, paramedics and medical officers, medical orderlies and both medical and non-medical specialists with qualifications in anaesthesia, emergency medicine and intensive care.

Beyond their medical qualification, the personnel deployed have to meet particular challenges: deployment on short notice in target regions around the world requires a correspondingly extensive tropical-medicine vaccination status. In order to be able to deal with the patient without being adversely impacted by poor weather conditions and during turbulence, the personnel must be very experienced fliers and, in particular, be free of kinetosis (travel or motion sickness) or fear of flying.

Confidently mastering the complex and differentiated intensive medical treatment of patients during flight requires the deployed medical and nursing staff to practise their skills every day. In other words: optimal safety and quality of treatment can only be achieved if all this is based on daily routine work, over many years, in intensive care and emergency medicine. For this reason, when appointing personnel to our medical crew we chiefly select staff from the anaesthesiology, intensive care and emergency medicine departments of our major military hospitals.

In order to respond to the specific requirements of particular scenarios, depending on the situation, a short-term change of personnel on board is possible. Thus the anaesthesia and specialist care team can be strengthened in number, with all 6 PTUs being used, and if necessary as the result of corresponding illnesses, a medical officer from another discipline (e.g. surgery, internal medicine, tropical medicine, etc.) can be added.

The course of a typical deployment and its special features

Depending on the situation of the event, its location and the number of patients to be evacuated, the deployment command is given either through the official military channel or, when civilian victims of accidents, attacks or disasters need to be treated, via the German Federal Foreign Office and a corresponding request for assistance to the Federal Ministry of Defence.

Flight planning and medical organisation are carried out simultaneously. Of the utmost importance is the earliest possible, precise information regarding the type and number of patients concerned, which is provided most effectively through direct contact between a competent medical contact person on the spot and the head specialist medical officer on board of the deployed aircraft. Everyday experience from the rescue service has shown that only by direct communication loss and falsification of information can be prevented.

Of course, planning is made more difficult when there is a disaster situation, as became particularly clear in the aftermath of the major tsunami in Indonesia. To clarify matters generally, let me explain how emergency medicine understands the term “disaster”: in addition to, in some cases, an extremely high number of victims, which always necessitates the involvement of foreign, often international aid workers, there is a collapse of infrastructure, whether in terms of means of transport or communication. Unfortunately, both of these are regularly to be observed e.g. in areas affected by earthquakes.

The aforementioned results in the following obstacles and special features, which require particularly profound experience in emergency medicine and intensive-care:

- Patients are often transferred in an unfamiliar environment, and in certain cases peace and order have to be re-installed under chaotic circumstances.

- What is the medical history of the individual patient, which medical findings are available, what therapy has already been provided, what are the special features in this case?

- Are previously adopted diagnostic and therapeutic measures adequate?

- Have the findings for one or more patients changed significantly, and in particular, has their condition deteriorated?

- Can an individual patient’s status be improved prior to transportation?

- In what sequence and with what priority are the patients to be treated? An especially important decision regards which patients require intensive-care places, which can adequately be treated “just” with intensive monitoring, and which patients can be transported on so-called “normal places”.

Experienced medical teams can normally handle such problems well as long as no additional obstacles arising from the disaster further complicate the situation. In light of the extremely high number of victims, the collapsed infrastructure and the unclear information situation, other fundamental issues arose for those on board the STRATAIRMEDEVAC flights within the framework of tsunami aid:

- When do the patients come, how many, where from and with which means of transport, and which injuries do these patients have?

- What is the best possible way of ensuring that the valuable patient transport places in the Airbus A-310 actually benefit the people most in need of them, and not the less severely injured, who can return to their home country later and by civil passenger aircraft without any detriment to them?

- What is the best way to proceed with the children of severely injured adults, so that these do not have to remain alone and unassisted in the country of deployment?

Outlook

Influenced by many factors such as the increased participation of Germany in international military deployments, but also by the, in international terms, outstanding emergency-medicine competence available, today the Federal Republic of Germany has at its disposal an airborne and medical transport system for the evacuation of large numbers of patients from remote areas that is seen by many as point of reference throughout the world.

Designed primarily to meet military needs, STRATAIRMEDEVAC has already been deployed on numerous occasions, including within the context of military emergency aid for civil populations, as well as after mass casualties in distant countries, following attacks whose victims included Germans, as support for friendly nations, during the River Elbe flood of 2003 and after the tsunami disaster. For us, it is essential to acknowledge and underline the enormous value that all German federal governments have placed on providing competent medical provision both for its soldiers deployed abroad and for its citizens within the context of exceptional mass casualties and disasters in other countries.

Authors

Colonel MC Prof Dr Lorenz A. Lampl

Head of Department Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine

born January, 17, 1955, Fürstenfeldbruck, Bavaria

1974 – 1981Medical School (Ludwig-Maximilians-University) in Munich, Germany

1979 Scholarship for the University in Vienna, Austria

1980 Graduation (State-Board) certified physician

1981 Doctorate

1994 Habilitation

since 1998 Head of Department Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine

Federal Armed Forces Hospital, Ulm, Germany

2001 Professor in Anesthesiology, University of Ulm, Germany

Address for the authors:

Head of Department Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine

Federal Armed Forces Hospital, Ulm, Germany

Oberer Eselsberg 40

D-89081 Ulm

Tel. +49 731/1710-2000 | Sekr. -2001, Fax +49 731/1710-2013

e-mail: lorenzlampl@bundeswehr.org

CO-AUTHOR

LtCol Dr Björn Hossfeld

Date: 07/08/2014

Source: MCIF 3/14