Article: MCM Bricknell1, NM dos Santos2

Executing Military Medical Operations

This paper concentrates on the regulation of casualties through the medical system. It considers the casualty flow throughout the system looking at how demand (or access), capacity and evacuation must be balanced. If the balance is broken, either the medical system has been over-resourced, which is inefficient, or the medical system has been overwhelmed, which is ineffective. Finally the paper discusses how the medical system should respond to a casualty surge.

Casualty Flow

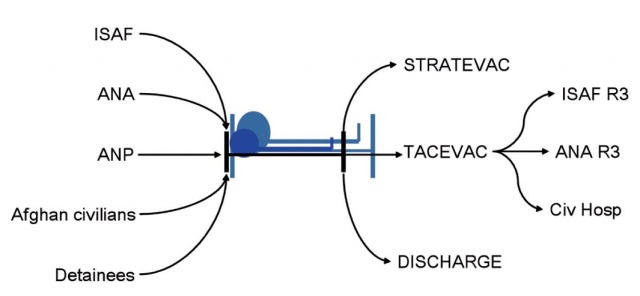

The management of medical operations can be considered as the relationship between three processes: demand, capacity and evacuation (Figure 1). The casualty estimate, including the whole Population at Risk (PAR) is the critical component of medical planning which determines the predicted demand. Medical resource planning will determine the capacity of the treatment system remembering that each group within the PAR may have differing medical treatment and evacuation requirements, with indigenous casualties likely to have a longer length of stay than international military casualties and different medical evacuation requirements. The movement of severely injured indigenous casualties is likely to be more difficult than international military casualties. The medical plan should ensure that these three processes are balanced. However the casualty estimate is only a prediction and the military maxim that ‘no plan survives contact with the enemy’ demands that medical staff actively manage the system. This is primarily directed by the Patient Evacuation Control Cell (PECC) through the management of both forward medical evacution (MEDEVAC) and tactical aeromedical evacuation (TACEVAC). The Medical Operations function should be thinking 12-48 hours ahead to answer the question ‘does the evidence of the medical workload for the last 24 hours suggest that there is likely to be any shortfall of capacity in the medical system in the next 48 hours?’

Figure 1: Casualty Flow – the relationship between demand, capacity and evacuation. If inflow increases or

outflow decreases then bed occupancy goes up. ISAF (International Security Assistance Force); ANA (Afghan

National Army); ANP (Afghan National Police); STRATEVAC (Strategic Evacuation); TACEVAC (tactical evacuation).

Figure 1: Casualty Flow – the relationship between demand, capacity and evacuation. If inflow increases or

outflow decreases then bed occupancy goes up. ISAF (International Security Assistance Force); ANA (Afghan

National Army); ANP (Afghan National Police); STRATEVAC (Strategic Evacuation); TACEVAC (tactical evacuation).

The medical system could be unbalanced because of either over- or under-capacity. If there is excess capacity (low bed occupancy) then the system is inefficient and too many medical resources have been deployed. The casualty estimate provides a prediction of the number of patients who require entry into the medical system, which is a single number based on a summary statistic of the precision of the estimate. The actual daily demand is likely to be highly variable, particularly in a counter insurgency (COIN) campaign. There may be occasions when the actual number of casualties exceeds the casualty estimate. If there is under capacity, occupancy is too high with insufficient beds to support the risk of casualties from future operations. This is clearly ineffective – and both militarily and politically unacceptable.

Controlling Demand/Access

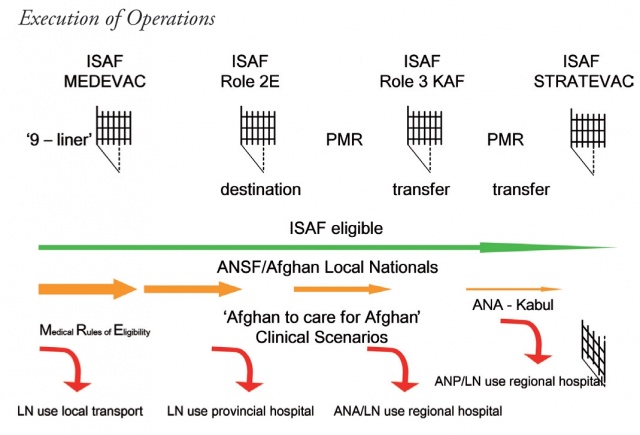

The strategic medical plan will define the patient groups who are eligible for access to the international military medical system which comprises initial medical evacuation, entry to first International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) hospital, in-theatre transfer to either ISAF or Afghan hospitals and strategic medical evacuation. The PAR is likely to include all international forces, international civilians supporting military forces, and opposing forces detained by the international force. In a stabilization or COIN operation, eligibility may be extended to indigenous security forces and the civilian population. There may be a substantial disparity between the capabilities of the international military medical system and the indigenous health system, however it is clear that the international military medical system cannot underwrite all of these deficiencies. This may cause ethical challenges such as that described by Henning in regard to intensive care [1]. This issue is summarised as ‘gate-keeping access’ (Figure 2).

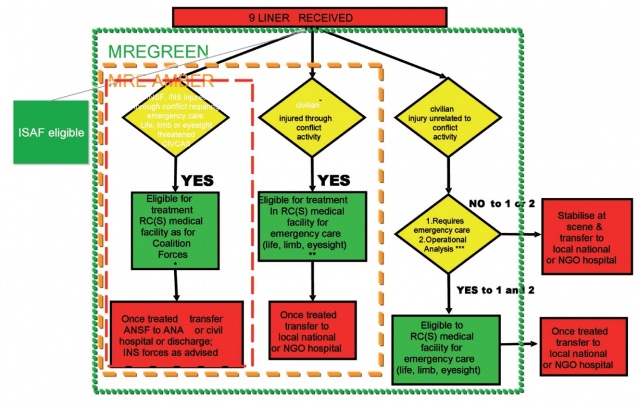

International forces are eligible for access to all aspects of the ISAF medical system including STRATEVAC, but as a matter of principle, Afghans are not evacuated from Afghanistan except in specific circumstances, perhaps under the care of an international, humanitarian Non-Governmental Organisations. Furthermore, Afghans should receive care from Afghans unless there are over-riding reasons why the international military medical system should provide this care. The medical system requires a management process that controls entry and can be adjusted according to capacity – this is known as ‘Medical Rules of Eligibility’ (MRE) (Figure 3). Control of medical evacuation through the ISAF system is balanced between increasing levels of care and the complexity for the family for supporting the patient. The reality is that all personal care for patients in Afghan hospitals is provided by family members and much of the in-patient medical care has to be paid for even in the ‘free’ public hospital system. Therefore the social costs of healthcare escalate in direct relation to the distance the patient moves from their locality.

The MRE process defines patient groups by their level of access to the international military medical system. International forces have absolute right of access. Indigenous security forces may have right of access for emergency medical care (life, limb or eye sight saving (LLE) care) in order to achieve the same effect on the moral component of their fighting power as the medical system achieves for international forces. It is unlikely the international medical system will provide routine medical care for indigenous forces. Care for indigenous civilians may follow the same principles but could be further limited to injury from conflict in order to reduce access for normal medical and surgical emergencies. The description and application of these rules have to be carefully balanced to ensure the international military medical system follows internationally agreed ethical principles and supports consent building without undermining the development of the indigenous health economy.

This diagram is colour-coded to allow an adjustment to the MRE for access by indigenous patients dependant on the unoccupied capacity in the medical system. MRE GREEN describes the normal situation in which Afghan civilians may be admitted for emergency medical care to receive LLE saving treatment. MRE AMBER excludes those Afghan civilians with LLE conditions that are not conflict-related unless by prior agreement with the Regional Command Medical Director and the hospital commander. MRE RED is imposed when the ISAF hospital system is full and therefore no Afghan civilians can be accepted unless injured as a direct result of ISAF actions. The MRE were further refined with clinical guidance for specific cases such as severe burns, closed head injuries with low Glasgow coma scales and neonatal emergencies. If the MRE is insufficient to control access, it is then necessary to examine whether the risk to security forces should be controlled in order to reduce demand for medical care.

Medical Capacity and Evacuation

The capacity of the medical system is determined by the medical resource analysis subsequent to the casualty estimate but actual demand is variable and dependant on factors such as operational activity, opposition activity, environmental conditions and incidence of disease. It is essential that the medical command system has accurate and timely information on bed occupancy in order to monitor the availability of unoccupied beds against the anticipated casualty flow. This is counter-intuitive. Although the clinical focus is on the care of those casualties who occupy the beds, the capacity of the medical system actually depends on unoccupied beds.

Monitoring the Performance of the System

The numbers of casualties moved by the medical system should be tracked within the time period determined by the casualty estimate. This allows a continuous rolling comparison between the casualty estimate and actual experience.

The frequency of reporting of bed occupancy should depend on the rate of change of demand and evacuation. This is not likely to be less than every 24 hours and may be as frequent as four or six hourly in periods of high casualty numbers. The percentage of beds occupied may be colour coded in order to give a quick assessment of the bed occupancy – e. g. <50% Green, 50-74% Amber, 75%-99% Red, 100% Black. In addition to daily reporting, it is also necessary to track the range of bed occupancy over a defined time period to determine if the mean occupancy is within the tolerance of the medical capacity requirement determined by the casualty estimate. It is likely that an increase in capacity is needed within the hospital system if the peak daily occupancy is above Amber. This is likely to be presented on a regular basis to the operational commander.

Another measure of hospital workload is surgical hours. This can be measured by the cumulative number of hours of surgery per surgeon, per surgical team or per patient. One measure of maximum productivity is seven hours of ‘skin to skin’ surgical time per surgical team per day. This assumes that pre and post operative clinical care, and surgical administration is also provided by the same surgical team with recognition that the requirement to conduct surgery varies across a 24 period. There also comes a point in surgical demand where surgical teams need to be rostered for shift work rather than routine ‘day working’. This would be when more than three surgical teams are required to meet the workload.

Figure 2. ‘Gate-keeping’ Access. MEDEVAC (Medical evacuation); PMR (Patient Movement Request); KAF (Kandahar Airfield); STRATEVAC (Strategic evacuation); ANSF (Afghan National Security Forces); ISAF (International Security Assistance Force); LN (Local Nationals); ANP (Afghan National Police); ANA (Afghan National Army).

Figure 2. ‘Gate-keeping’ Access. MEDEVAC (Medical evacuation); PMR (Patient Movement Request); KAF (Kandahar Airfield); STRATEVAC (Strategic evacuation); ANSF (Afghan National Security Forces); ISAF (International Security Assistance Force); LN (Local Nationals); ANP (Afghan National Police); ANA (Afghan National Army).

The aeromedical evacuation requirement can be tracked using a hospital status report that provides a bed census by patient with the evacuation plan (aeromedical evacuation, ground evacuation and discharge). This can be used to forecast when occupied beds will be vacated and should be matched to the medical evacuation requests as they are submitted. The periodic hospital commander’s Medical Situation Report (MEDSITREP) provides a summary of the data described above and the commander’s assessment of the match between the hospital capacity and workload.

Response to a ‘Casualty Surge’

Whatever the medical plan, there will be a finite limit to the capacity of medical assets under a medical commander. Therefore it is possible that the medical system may become overwhelmed through either a single medical major incident, or else through a protracted series of high casualty events. The term ‘casualty surge’ is chosen to encompass both of these scenarios. Neither of these is necessarily a Mass Casualty (MASCAL) event. The term MASCAL has a specific military meaning in which there is an excessive disparity between casualty numbers and medical capacity such as after a nuclear or chemical attack [2]. In these circumstances the triage categories change from P to T and care is provided on basis of the greatest good to the greatest number rather than to the sickest first. The use of the term MASCAL to describe a specific incident is only authorised by the chain of command on advice from the theatre medical commander.

Figure 3: International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Medical Rules of Eligibility (MRE). RC(S) (Regional Command (South)); NGO

(Non-Governmental Organisation); ANSF (Afghan National Security Forces); ANA (Afghan National Army); INS (Insurgency). *

consider medical evacuation direct to ANA hospital, **consider referral to local civilian hospital, ***Operational Analysis – does

the ISAF medical system have sufficient capacity for ISAF forces?

Figure 3: International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) Medical Rules of Eligibility (MRE). RC(S) (Regional Command (South)); NGO

(Non-Governmental Organisation); ANSF (Afghan National Security Forces); ANA (Afghan National Army); INS (Insurgency). *

consider medical evacuation direct to ANA hospital, **consider referral to local civilian hospital, ***Operational Analysis – does

the ISAF medical system have sufficient capacity for ISAF forces?

The term ‘Medical Major Incident’ is taken from Medical Major Incident Management and Support (MIMMS) to describe a single of incident or multiple incidents in a short timeframe where the location, number, severity or type of casualties requires extraordinary medical resources to resolve [3]. In the military environment, it is essential to add the adjective ‘Medical’ as there may be other types of major incidents that require extraordinary resources to resolve but have less impact on the medical services. The PECC in the Combined Joint Operations Centre should detect the possibility of a medical major incident through the reporting of events by the operations staff. They should follow the standard actions of a Silver or Gold command as described within the MIMMS framework. The first action is to issue the standard codewords to inform the medical system (Major Incident – Standby, Major Incident – Declared, Major Incident – Stand down). The response options are: to surge medical treatment capabilities to assess the situation and provide on-scene medical carer, to surge medical evacuation to clear the point of injury and to regulate the patient load across the medical system both by regulating to initial destination and re-distribution between hospitals.

A sustained high rate of casualties beyond the casualty estimate may not cause a medical major incident but could cause a rise in the bed occupancy and surgical activity. This in turn may reduce the capacity of the medical system to respond to a medical major incident and may also place excessive strain on the medical personnel in the system. The most immediate response is to increase the evacuation capacity of the system and to reduce the Theatre Patient Holding Policy, thus increasing the throughput in the system by reducing hospital length of stay. The enduring solution is to increase hospital capacity by reviewing the casualty estimate and medical resource requirement. It is useful to develop a series of triggers to provide medical augmentation until the full analysis can be performed (Box 1).

• If the Hospital commander requests assistance

• If surgical teams have three or more consecutive days of more than ten hours of surgery

• If ICU bed capacity exceeds 75% bed occupancy for more than three days

• If ICW bed capacity exceeds 75% for more than three days

• If the average for 0600 reported ICU bed occupancy exceed 75% for more than 50% in a two week rolling average

• If the average for 0600 reported ICW bed occupancy exceed 75% for more than 50% in a two week rolling average

It is vital that the most probable and most dangerous casualty surge scenarios are included as specific contingency plans within the Standard Operating Procedures of the medical staff. They should be regularly rehearsed as both tabletop exercises and field exercises.

Conclusion

This paper has described how the regulation of casualties through the medical system is actually achieved. Demand (or access), capacity and evacuation must be balanced. It has covered the concepts of ‘gate-keeping’ access and the medical rules of eligibility. Measures of performance of the system have been discussed including bed ‘unoccupancy’ and surgical hours. The final section of the paper examined the responses to a casualty surge including deploying medical assets to the incident, regulation of patients and augmenting the capacity of the medical system.

References with the author.

MCM Bricknell, Colonel

1Medical Director, Headquarters Region Command (South), Operation HERRICK, BFPO 772;

Co-Author:

NM dos Santos

2Headquarters Health Services Wing, Royal Australian Air Force, RAAF Base Amberley, QLD, Australia

Date: 07/10/2012

Source: MCIF 2/12