Article

Caring for Compatriots

Military Necessity before Medical Need?

Medical ethics prohibits preferential care for patients. All must be treated on the basis of medical need alone. In military medicine, however, particularly during war and when resources may be scarce, ethical principles may dictate preferential care for compatriot soldiers. In these cases, military necessity and the ethics of friendship and comradery dictate a different set of duties for comrades-in-arms. When these individuals require medical care, there are sometimes solid moral grounds to treat fellow soldiers before of enemy or allied soldiers regardless of the severity of their wounds.

As it considered military medical ethics, the World Medical Association (WMA) declares

Ethical principles of health care do not change in times of armed conflict and other emergencies and are the same as the ethical principles of health care in times of peace.

What is behind the assertion that medical ethics does not change in time of armed conflict? One answer may be the universality of medical ethics principles. Norms such as the duty to do no harm, to provide impartial care to the sick and injured, and to respect a patient’s dignity, autonomy and privacy should not vary according to circumstances. Thus the ethics of psychiatric, neonatal, pediatric or geriatric medicine, for example, are all the same. The circumstances vary, as do the conditions of the patient, but the ethics of medical care remain constant.

One is tempted, as is the WMA, to draw the same conclusions about military medical ethics and to see service personnel as simply another kind of patient. During peacetime this is true. In many countries, service personnel and their families receive medical care from military medical organizations in the same way that nonmilitary civilians receive their care from the national health care system. And, in many cases, facilities overlap, particularly when government hospitals provide care to military and civilian patients alike. Under these circumstances, the principles of medical ethics apply equally. Each patient, whether military or civilian, is treated in accordance with the principle of medical necessity that mandate care on the basis of a national plan that balances lifesaving care with quality-of-life care. To act otherwise would invite charges of bias and partiality However the situation changes dramatically during wartime and, in particular, on the battlefield where the principle of military necessity may conflict with and sometimes overwhelm the principle of medical necessity. In the sections below, I will first discuss the principle of military necessity and then explain how it affects patient care and patient rights during wartime.

Medical Necessity and Military Necessity

Military necessity is often defined as “The means necessary to subdue an enemy and which are not forbidden by international law” (Additional Protocol I, 1977, Article 35). There are two difficulties with this definition. First, it ignores the legitimate goals of war for which one subdues an enemy. Legally ignoring a nation’s war aims is sometimes necessary because it is often difficult to discern where justice lies in practice. As a result, the law treats all combatants on the field equally as long as they do not commit war crimes. But morally, there is good reason to limit necessity only to those belligerents, whether a state or non-state (such as a guerrilla organization), who fight for just cause. Just cause includes fighting in self-defense or in defense of foreign citizens who face grave human rights abuses at the hands of their own government (as was the case in Libya or Kosovo, for example). On this reasoning, an oppressive regime like Syria cannot appeal to military necessity to justify its military operations. In this case, no military action whatsoever can be necessary. Second, restricting military necessity to means not forbidden by international law begs the question. The vexing question is often: when may military necessity permit a belligerent to override international law and resort to prima facie unlawful or unethical means of war? Put differently, is it sometimes permissible to violate international law or a principle of medical ethics when militarily necessary? The answer is “sometimes.” Sometimes, as I will show in the cases below, it may be permissible to treat soldiers based on their identity rather than on the basis of military need. To see how this occurs, it is important to compare military and medical necessity.

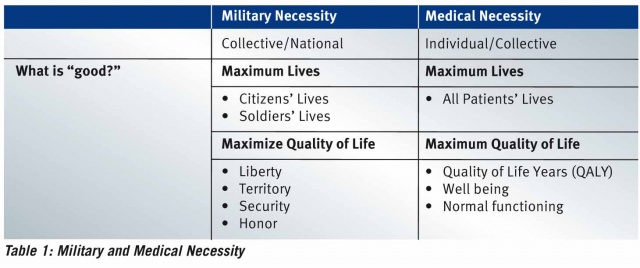

Table 1 distinguishes between military and medical necessity (Table 1).

Table 1 highlights two points. First, military necessity favors collective interests of a state or a people over the individual interests of many of their citizens. As a result, it is common in wartime to enlist or conscript citizens for military duty where they will risk their lives to safeguard national security. To accomplish this end, policy makers, politicians and military officials are charged with defending the collective welfare. Medical necessity, on the other hand, is radically individualistic. Health care providers serve the needs of individual patients. To do this, a national health care system is expected to provide sufficient resources to care for all citizens equally according to their medical needs. No one is expected to sacrifice his or her interests for some greater good. There are, however, collective constraints. Certainly the funds allocated to medical care must meet some standard of justice that allows the state sufficient resources to fund other essential services such as welfare, education or security. Medical care is, therefore, limited. Moreover, individuals cannot be expected to bankrupt the system. The state will not treat every illness. Nevertheless, the state will endeavor to provide each individual with the best care possible. To accomplish this end, health care professionals are charged with the caring for their patient as beneficently and professionally as possible.

The second point of Table 1 pertains to the definition of good that each kind of necessity serves. Both military and medical necessity hope to maximize the number of lives saved (of some individuals) and the quality of life (of other individuals). But the criteria for each are different. During war, military necessity compels the state to sacrifice soldiers to save civilians, while medical necessity usually makes no distinctions between the lives it saves. Medical necessity serves all patients. At the same time, military and medical necessity each strives to maximize quality of life. But here, too, each defends a different kind of life. The state defends its collective, political life while medical necessity endeavors to save or improve an individual’s human life. As such, the idea of quality of life differs when considering military or medical necessity. The quality of political life depends on many things such as liberty, territory, security and honor and whose value often supersedes that of individual lives in war. How many lives a nation will risk for these goods is a decision that a body politic must make when it goes to war. Medical quality of life is, of course, more narrowly focused and includes measures of happiness, pain, suffering, mobility, day-to-day functioning, and access to continuing care. Here, too, a society may allocate funds to enhance quality of life at the expense of costly care that may save some lives. There are no hard or fast rules to balance life and quality of life. Each society chooses on the basis of universal human rights and parochial concerns and norms. Nevertheless, political life provides the vehicle to sustain individual life and, therefore, will often take precedence when the political and the individual life conflict as they often do during war.

The relationship between military necessity and medical necessity is therefore complex because it pits different interests (collective and individual) as well as different goods (military/political/medical life and quality of life) against one another. To better understand the relationship between the two kinds of necessity and their impact on international law it is important to see how the principles play out in the field. One relevant example is the provision of care for the wounded. Here the question is: May military necessity permit medical personal to treat compatriots first rather than according to medical need as the principles of medical ethics demand?

Medical Care for Compatriots during Wartime

The iron rule of medical treatment during war is clear:

“Members of the armed forces who are wounded or sick shall be treated humanely and cared for without any adverse distinction founded on sex, race, nationality, religion or any other similar criteria… Only urgent medical reasons will authorize priority in the order of treatment to be administered (Geneva Convention (I) 1949, Article 12)

To avoid any misunderstanding, the Commentary to Article 12 makes the following point: Each belligerent must treat his fallen adversaries as he would the wounded of his own army.

Military medical personnel know the law but remain bound to an equally demanding rule: “Compatriot care, above all else.” The reasons for preferring compatriots to enemies turn on military necessity and an obligation to care for one’s compatriots when their lives are at risk.

All military medical organizations recognize that battlefield circumstances may demand that physicians dedicate scarce medical resources first to those they can return to duty and only then to those whose lives and limbs are at risk. An oft cited case describes ‘penicillin triage’ during WWII when, in 1942, military physicians used scarce penicillin to cure gonorrhoea stricken soldiers and return them to duty before treating those with more extensive battlefield injuries who would never return to battle.1 Here, it is clear. Military necessity demands treating less critically wounded soldiers who can make a substantial contribution to the war effort at the expense of those who need life-saving care. This upends the ethical principle of impartial treatment based on medical need.

Similarly, medical operations in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2001 also placed a priority on military necessity. Although military organizations have contingency triage plans to prioritize care, the hard moral cases – having to choose between saving the lives of severely wounded soldiers or returning the moderately wounded to duty – are relatively rare.2 More common are questions about providing care to local civilians caught in the cross fire or caring for “host country” personnel who fight alongside US and NATO troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

To support its soldiers, The US Army, for example, provides medical care at several levels. The Battalion Aid Station provides first aid and transport, the 20 person Forward Surgical Team offers immediate treatment, surgery and evacuation to a 248 bed Combat Support Hospital that provides resuscitation, reconstructive surgery, intensive care and psychiatry. And, when necessary, the wounded receive sophisticated treatment at a full service trauma center in Landstuhl Germany or in the US.3

While this system is designed to provide the best possible care for US soldiers, American medical facilities also care for host-country soldiers and local civilians wounded during American operations. While severe American casualties evacuate to superior medical facilities, local military casualties must turn to a poorly functioning local system for further care. This two-tiered system limits care for host country wounded who, without access to sophisticated prosthetic devices, for example, will not receive the same reparative surgery US soldiers receive in the field. Host country civilians fare even less well. Coalition forces do not maintain facilities to care for local civilians and sometimes find it necessary to turn away civilian patients. Nevertheless, Coalition forces will treat civilians caught in the cross fire to the extent of saving the ‘life, limb or eyesight’ of host-nation wounded.4 This is by and large emergent care; there are very few facilities for follow-up or chronic care. Nevertheless, two situations stand out. First, pediatric cases present a special challenge. Alert to the adverse publicity of failing to provide anything less than maximum care for children, US medical facilities often offer extensive and sophisticated care to children.5 Second and no less problematic is the care due to detainees. As prisoners of war, detainees are entitled to the same care provided Coalition soldiers and therefore receive better care than host country allies. There are, therefore, at least 4 or 5 different classes of medical patients: coalition soldiers, detainees, host nation soldiers, host nation civilians and, sometimes, children. All will receive different levels of care for identical injuries.

As this description suggests, it is not always possible to treat the wounded strictly on the basis of medical need. Availability of follow up resources, clearly a function of national identity, dictates the care the wounded receive at the onset. Similar cases may not be and, perhaps, should not be treated similarly.6 This is, however, a prima facie violation of the neutrality provision of the Geneva Conventions which prioritize care solely on the basis of medical need. And although some commentators view the obligation to preserve neutrality and treat indiscriminately as absolute,7 situations arise in wartime that temper this assessment. First, the obligation to treat those who can contribute best to the war effort may override the duty to save lives when resources are scarce.8 Second, medical personnel may apply an ethic of comradery or ethic of care and treat their own soldiers first regardless of the severity of their wounds because of a special obligation they owe compatriots. 9

Obligations toward comrades also portray the reach of military necessity. Consider the following case:

One US soldier and one Iraqi Army allied soldier present with a gunshot wound to the chest. Both have low O2 saturations. There is only enough lidocaine for local anesthesia for one patient, and only one chest tube tray. One will get a chest tube with local anesthesia, and the other will get needle decompression and be monitored by the flight medic.10

Who gets the Chest Tube and Local Anesthesia and why?

When participants in an American workshop were asked how they would resolve the issue, their answer was unequivocal: “The wounded American.” When I asked why, their answer was equally as confident: “Because he’s our brother.”

It appears, then, that military medical personnel are of two minds about the Geneva Conventions. On one hand, they acknowledge the principle of medical impartiality. On the other, they recognize a conflicting and often overriding obligation to provide their compatriots with the best medical care possible. The first principle requires little justification. Medical integrity and efficiency depend upon treating the neediest cases first regardless of rank, gender or nationality. The second principle, however, is also compelling: armies go to war to win. Winning requires fit troops and fit troops require superior medical care. It is therefore advantageous and, indeed, proper to treat compatriots first when resources are scarce. This is the reasoning behind battlefield and penicillin triage where during war and when resources are scarce, many armies permissibly reverse their order of treatment and treat the neediest last. Instead of treating those cases most medically urgent, medical personnel will see to those who can return to battle the quickest. This means that some otherwise treatable patients will die while others, whose treatment might be delayed, will enjoy immediate care so they can fight on. The underlying logic is utilitarian and morally sound: without reversing the order of treatment, troop integrity will suffer and military capabilities may falter. The outcome, defeat, is the worst possible. By this reasoning, injured enemy soldiers also move to the rear of the queue.

A similar but more complex logic drives the decision to treat one’s brother-in-arms before all others in the case just outlined. There, the two patients were allies, not enemies. The military benefit of saving both was presumably equal. Still, caregivers express a distinct preference for their compatriots.

One reason is clearly utilitarian. Military sociologists have long noted the importance of “primary” bonding among soldiers and officers particularly at the platoon level (40–50 soldier units).11 Primary bonding begins with teamwork and interdependence and slowly grows to engender trust, loyalty, shared commitments, mutual assistance and self-sacrifice. Small military unites are not merely a collection of well-coordinated, self-interested individuals, but a cohesive band of brothers distinguished by a new identity: comrade-in-arms. In this tight knit environment, preferential treatment for comrades-in-arms is militarily advantageous because it preserves morale and a unit’s fighting capability.

There is, however, an additional duty that obligates some military personnel no less than the principles of medical ethics. This obligation transcends utilitarian justice and its emphasis on distributing scarce resources efficiently and fairly and, instead, underscores the special relationships individuals have with those who are close and to whom they owe a special obligation of aid regardless of cost and competing claims.

It is not hard to understand how preferential treatment for family and friends is a fundamental moral obligation. Parents are not expected to invest much in the care of others before they attend their own children. Friends, likewise, have special duties toward one another that they do not have toward strangers. These are common-place intuitions and underlie what the philosopher Virginia Held calls the “ethics of care12”. The ethics of care invokes unconditional duties that individuals owe one another by virtue of a special relationship between those who can provide life-sustaining care to those who need it. The ethics of care reflects an emotive rather than contractual bond that calls for “personal concern, loyalty, interest, passion and responsiveness to the uniqueness of loved ones, to their specific needs, interests [and] history.”

Guided by preferential principles, special obligations toward friends, family and compatriots inevitably raises questions of distributive justice: what if others are in greater need of care and attention? This is a compelling question but the ethics of care is not about justice. Friends and family should aid one another without expectation of payment in kind, often at great personal cost and when knowing that the same aid might benefit a stranger more. To think too hard about rescuing a stranger when the lives of one’s family or friends are in danger is, as Bernard Williams famously put it, “one thought too many.” Is medical care for enemy wounded also “one thought too many”? If primary military units are like families, preferential treatment for compatriots may be as morally obligatory as those toward family members. The ties that bind comrades-in-arms are no different than those binding family members or friends and speak to an unconditional and unilateral obligation to help one another in need.

Transposed to the battlefield, the ethics of care has important ramifications. Consider three different scenarios.

Equal Injuries

In the case study from Iraq, both soldiers had similar wounds and an equal chance of survival. They were allies and saving one offered no superior military benefit. In the case of a tie, one could flip a coin and while a lottery accords with impartiality, it ignores the moral significance of the duties imposed by primary group membership. These duties are not negligible but should only serve as a tiebreaker after all other impartial criteria of distributive justice are exhausted. In this case, then, treating the American first because he is a comrade-in-arms is morally permissible.

Grossly Unequal Injuries

Medics sometimes insist that they would treat a compatriot’s slightest wound before attending to the enemy. On reflection, however, what they mean is that they will stabilize one’s compatriot first and then attend the enemy if their compatriot’s wound is slight and the enemy faces severe injury or loss of life. In this case, the ethics of care is trumped by a different concern, namely the “rule of rescue,” that is, the obligation to aid others when the cost is reasonable and the danger to strangers is very great. On the battlefield, however, and without sophisticated diagnostic equipment or expertise, the relative severity of a soldier’s wounds may not be readily apparent to the field medic. This may lead medics to treat on the basis of the category I, wounds of equal severity, or on the basis of category III, wounds that are only moderately unequal. Either case may justify preferential treatment for compatriots.

Moderately Unequal Injuries

These are the hardest cases. Consider the following:

- There are sufficient medical resources to save the life of one compatriot or two (or more) enemies.

- Compatriots face disfigurement or loss of limb while enemies face loss of life.

Normally, the moral choices are clear. Saving two lives is better than saving one life; saving lives is more important than saving limbs. Nevertheless, the ethics of care may permit different judgments. In some cases, it may be morally permissible to save the life of one compatriot rather than the lives of two or more strangers (whether enemies or allies). Similarly, limb may sometimes trump life.

Why is this so? One reason invokes the parent who, acting on the compelling demands of the ethics of care will prefer the welfare of her child at the cost of many other lives. Beneficence, the duty to aid others, weakens considerably when the costs to the rescuer are onerous as they will be if the rescuer faces losing a child or other primary group member. When lives are at stake, our duties to friends and family are clearest and even the possibility of saving the lives of many strangers will not override a parent’s (or soldier’s) duty to save his own child’s (or compatriot’s) life.

When limbs are at stake, one can imagine several scenarios. In one, an artificial limb will restore significant functioning so that compatriot limbs do not trump enemy lives. But one might also imagine a situation where loss of limb severely impairs one’s prospect of a decent life and here, the obligations that come from primary bonds may afford attention to limb over life.

Beware the Slippery Slope

A word of warning about giving too much weight to friends and family. While primary bonding is both essential for effective fighting and forges special and overriding moral obligations among group members, it cannot allow group members to run roughshod over fundamental moral norms or permit abject neglect. As doctors, nurses and medics provide care to compatriots, the ethics of care requires attention to the plight of strangers and reflects concern for basic human rights and what Held calls “moral minimums” of care.

Medics recognize this they report a readiness to stabilize or sedate severely wounded enemy soldiers while they first attend to the less serious wounds of their compatriots. It also explains why medical personnel might treat wounded compatriots before wounded enemy soldiers but refrain from treating compatriots once they have already begun to treat wounded enemy soldiers. This may happen when surgeons begin caring for enemy soldiers only to be suddenly faced with an influx of their own. Anecdotal accounts suggest that doctors and nurses would not cease caring for an enemy to provide for their own soldiers. Apart from a justified concern that withdrawing care is akin to murder, it is also clear that medical personnel enter into a special relationship once they begin treating any wounded soldier. This new relationship carries strong obligations of care of its own that cannot be readily abandoned.

When resources are limited, hard moral dilemmas bedevil military medicine. Even when funded by a country as wealthy as the United States, wartime medical care is plagued by scarcity. Under these circumstances, providers are often torn between the norms of law and the ethics of care. These are not easy dilemmas to resolve but in cases like those described, medics, nurses and doctors should feel no moral compunction about providing priority care to compatriots.

Conclusion

War presents special challenges to medical ethics because military necessity and special obligation of care may override the principle of medical necessity and impartial treatment. The case described above is not the only time that military necessity may affect the principles of medical ethics. Other cases will include the imperative to develop certain kinds of nonlethal weapons to help wage war more effectively; force feeding hunger striking detainees who risk their lives to pursue a political or military goal or developing enhancement technologies that use medical interventions to improve military capabilities.13 In each of these cases, and others, military physicians must wrestle with their obligations as military officers and as care givers. n

References: ref@mci-forum.com

Date: 08/18/2017

Source: MCIF 3/16